1960 European Nations’ Cup

Host: France

Winners: Soviet Union

Like the World Cup and the European Champion Clubs’ Cup before it, the European Nations’ Cup (as it was then known) was the brainchild of a Frenchman, in this case Henri Delaunay, the secretary of the French Football Federation. The tournament was almost stillborn as it struggled to gain the required sixteen entrants, with all the British countries along with Italy and West Germany sitting it out.

The tournament was structured vastly differently back then: only

seventeen countries entered it in the end, and the teams played

two-legged home and away fixtures until the semi-finals. And it was only

when the final four was set that the host was chosen.

It all begun with a bang, as 100,572 people crowded into Lenin Stadium

in Moscow to watch the Soviets beat Hungary 3-1 in September 1958. This

was just the start of a long route to Paris for the final almost two

years later, as the inaugural European Nations’ Cup was soon pockmarked

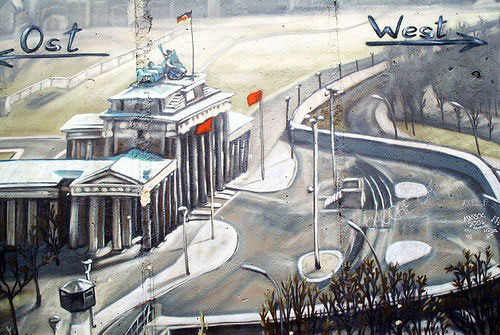

by Cold War politics.

After going on to beat Hungary 4-1 on aggregate, the Soviet Union were drawn against Spain in the quarter finals. But General Franco refused to allow the Soviets into his country for the first leg, forcing Spain to withdraw. This put the Soviets into the semi-finals, where they brushed aside Czechoslovakia 3-0.

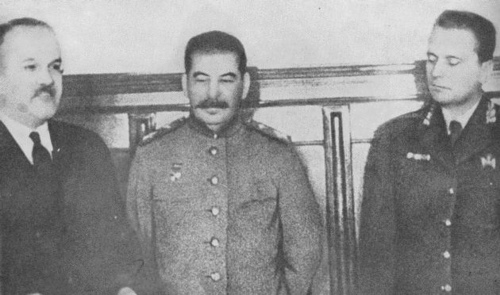

Franco’s controversial decision was a reminder that a football tournament featuring East and West European nations would have been unthinkable just a decade earlier. The slight easing of East-West tensions as the 1950s progressed, after the death of Stalin and the end of the Korean War (both in 1953), transformed the possibilities for intra-European sport.

In fact, historian Antonio Missiroli has even argued that the development of the European Champions’ Cup (now Champions League), the Inter-Cities’ Fair Cup (now UEFA cup) and the European Nations’ Cup signified a certain “anticipation” of the developing lines of European history and politics.

The

Soviet success was not a great surprise. Whilst never as consistently

competitive in football globally as it was in ice hockey, this was a

strong era with Lev Yashin inspirational in goal. After entering their

first international competition at the 1952 Olympics, they won gold at

the same tournament four years later, and would reach the semi-finals of

the World Cup in 1966.

The

Soviet success was not a great surprise. Whilst never as consistently

competitive in football globally as it was in ice hockey, this was a

strong era with Lev Yashin inspirational in goal. After entering their

first international competition at the 1952 Olympics, they won gold at

the same tournament four years later, and would reach the semi-finals of

the World Cup in 1966.

In between, 1960 was perhaps the peak as organised sport in the U.S.S.R. had solidified in the era of postwar reconstruction in the 1950s, and was entering a period of remarkable growth — over 2,000 stadiums would soon be built. Attendance had tripled in the Soviet league in the 1950s, reaching over ten million annually. By 1960, football was televised in Moscow.

The team picked in 1960 was the first to really look beyond the Moscow-based clubs and draw from the talent available elsewhere. This approach would be increasingly important for Soviet teams in later decades.

But it was Lev Yashin, from Moscow, who was the team’s heart and soul at the 1960 tournament. I can’t do a better job of describing him than Eduardo Galeano has in Soccer in Sun and Shadow:

When Lev Yashin covered the goal, not a pinhole was left open. This giant with long spidery arms always dressed in black and played with a naked elegance that disdained unnecessary gestures. He liked to stop thundering blasts with a single claw-like hand that trapped and shredded any projectile, while his body remained motionless like a rock. He could deflect the ball with a glance.

It took Yashin’s spidery best to keep Yugoslavia at bay in the final, for Tito’s nation were their biggest competitors both politically and in footballing terms in Eastern Europe. They would reach the Olympic final four times in a row from 1948-1960, finally winning it in Rome a few months after the European Nations’ Cup ended.

And by the 1960 European Nations’ Cup final, the Yugoslavs had already demonstrated their firepower: after brushing aside Bulgaria in the preliminaries, they headed to Belgrade for the second leg of their tie with Portugal 2-1 down. By halftime they had erased the deficit, and they poured in three goals in the second half to set up a semi-final with France.

It what must be one of the most exciting semi-finals ever seen, witnessed by a mere 26,370 in Paris despite the presence of the home team, Yugoslavia prevailed in a titanic battle featuring nine goals scored by seven different players.

France seemed to be on their way to victory when they went 4-2 up in the 53rd minute, thanks to goals from Vincent, Heutte and Wlsnieski (2). Then all hell broke loose between the 75th and 79th minutes: Jerkovic scored twice and Knez once as the Yugoslavs tore apart a shellshocked French team to clinch a 5-4 victory.

The final between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia could only be something of an anti-climax after that game, despite the political tensions — based off the Tito-Stalin split, though relations had improved somewhat after Nikita Khrushchev took over the Kremlin — bubbling under the surface.

In front of just 17,966 in Paris, Milan Galic opened the scoring for the Yugoslavs just before half-time. The Soviets pulled level in the 49th minute thanks to Torpedo Mosvow’s Slava Metreveli. The winning goal in the first European Nations Cup final came deep into extra time, when SKA Rostov-on-Don’s Viktor Ponedelnik headed home to win the Soviets first and ultimately only major championship.

photos

| Ranking | Player | Country | GS (PEN) |

- Year

- Winners

- Runner-up